The movement known in Catalonia as modernism was born in Europe at the end of the 19th century and the start of the 20th century as an opposition to realism or naturalism. Although this new cultural movement affected new forms of expression and in fact all manifestation of art and thinking, it is in architecture and the decorative arts where the full meaning can be seen.

Its name varies between certain countries; jugendstil in Germany, secessionism in Austria, liberty style in Italy, modernismo in Spain and art nouveau in France and England (also; modern style). These tendencies are not exactly identical in each country; however they coincide in era and have similar esthetic values.

We can consider modernism as a response to the industrial revolution and its advances therein, such as electricity, the railways and the steam engine. Changing dramatically the way of life in a city and the population of such, the industries thus created a wealthy bourgeoisie. Modernism is therefore, an urban and bourgeoisie style.

In Barcelona’s case, the beginnings of modernism coincided perfectly with the expansion plans for the city at the end of the 19th century, after the removal of the city walls that suffocated the city in 1854. This city growth represented an unbeatable opportunity for the bourgeoisie to be able to satisfy their yearning for modernisation, to express their Catalan identity and to display their wealth and distinction. An example of this can be found in the patronage of high bourgeoisie, such as Count Güell and Gaudí.

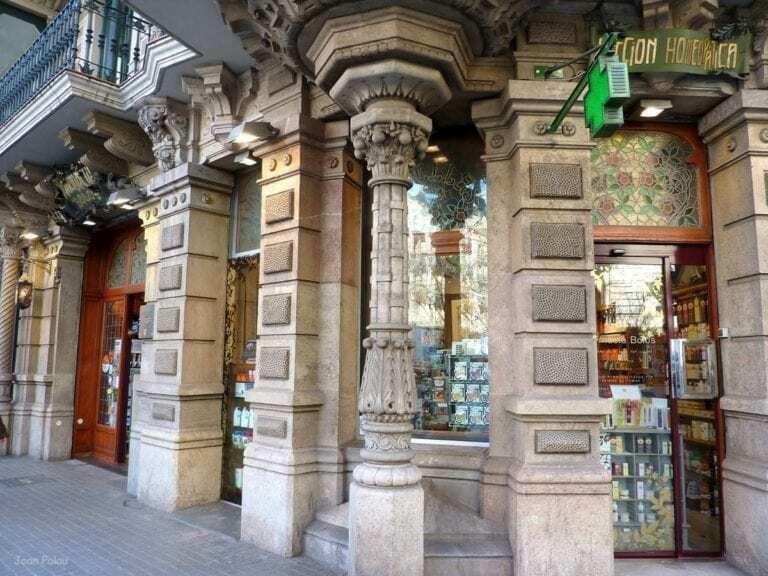

The modernist architecture in Catalonia united the most up-to-date construction techniques (the use of steel structures and pre-fabricated elements) with traditional elements (visible brick) and links to the gothic style to keep a certain parallel. It is a decorative architecture, integrating all aspects of the arts. Architects and their sculptors situated birds, butterflies, leaves and flowers as decorative elements on the exterior of the buildings, taking the form of motifs or ornament in stone and pottery. Larger figures in the form of fabulous animals or persons are also placed in the cornices as coloured ceramics. Windows and balconies are structures of forged steel and are artistically elaborated. The modernist style has not always been celebrated within cultural Catalonia. It is surprising to read articles by the likes of Carles Soldevila, Josep Pla or Manuel Brunet asking for the removal of the ‘Palau de la Musica’, considering it an architectural aberration.

Noucentisme (New Classicism), the movement which succeeded modernism, considered the former to be of bad taste and many shops and commercial buildings were transformed to look more austere and discreet. One of the most representative cases of this was the modernist amputation suffered at street level, of the Casa Lleó i Morera.

Origin

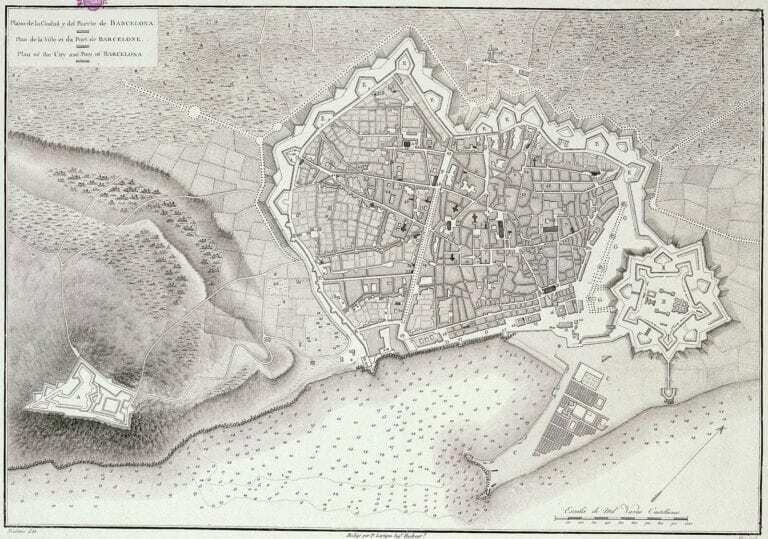

We find the origin of the Eixample in the previously Barcelona’s old city walls, between the city and the adjoining villages. In previous times this was a military zone, and the extensive area was not built on – instead it was being used by the farmers of Gracia and Barcelona as orchards and gardens.

Until the beginnings of the 19th century, the medieval walls of Barcelona were sufficiently sized to accommodate the city as it grew, but at the time of the industrial revolution the city surpassed this boundary, with the arrival of new factories and a heightened population.

Owing to the prohibition to build outside of the city walls, these factories and worker’s neighborhoods were built in the villages surrounding the city. Settlements such as Gracia, Sants, Sant Martí and Sant Andreu became industrial towns.

In the short progression period of 1854 and 1856 the city walls were removed, but it wasn’t until 1858 that the new urban planning was approved to extend the city.

In 1860 the plan was entrusted to Idelfons Cerdà, who was obsessed by the city's lack of sanitation inside the city walls, so that the plan made maximum use of the direction of the winds for greater oxygenation and assigned a key role in the parks and gardens of the interiors of the blocks. Concerned also by the mobility, it defined a width of streets out of the normal thinking on a motorized future and also incorporating railway lines. The Plan Cerdà was an extension between Montjuïc and the river Besós, including the Sant Martí term.

Following the Cerdà plan, the neighborhood was built with money from the rich families of Barcelona. The bourgeois of the city competed in the esthetic refinement of the construction of their houses with facades profusely decorated with diverse materials like ceramics, leaded glass or cast iron. We can see it in many modernist buildings made by architects such as Puig i Cadafalch, Domènech i Montaner or Gaudí, among many others proliferate.

The entirety of the Eixample area constitutes an art nouveau or modernist architectural style that is unrivalled in Europe.

The Cerdà Plan

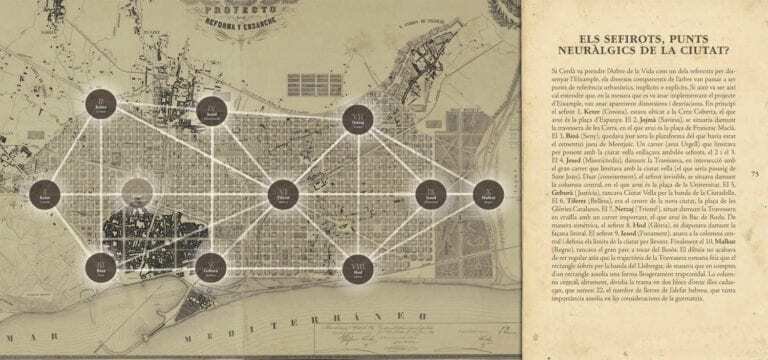

With his urban plan, Cerdà wanted to design an equalitarian city, that didn’t differentiate between neighbourhoods for their stature or life quality. The same services were to be present uniformly in all corners of the city.

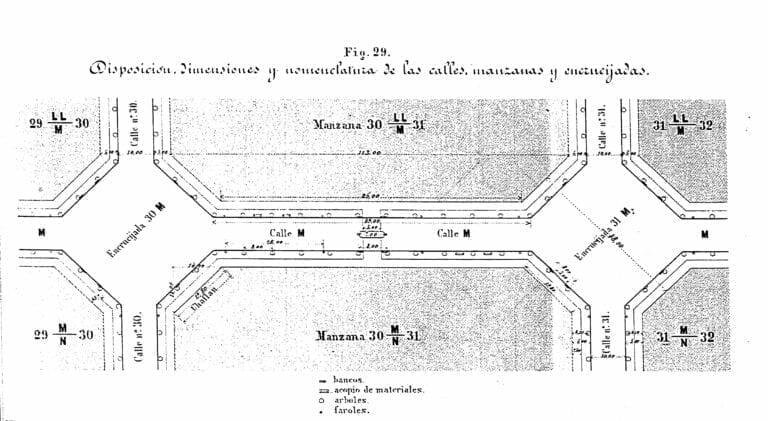

He based this idea in a huge network of perpendicular and transversal streets, all of which uniform, except for two biased and overlapping avenues; Diagonal and Meridiana, along with Gran Vía which bisects the city. The meeting point for these axis was at the central communication point of Eixample; the sprawling square of Las Glories. All of Barcelona’s new service points, such as markets, social centres and churches were rigorously planned and distributed, along with the city parks.

The blocks of the streets were not exactly squared. To increase visibility the corners were cut off or chamfered. In the interior of the blocks there were only one or two sides and the rest was to be left as community gardens. The houses were not to be more than three levels high (16 metres), nor were they to have too much depth. Cerdà established this because he considered that the health of Barcelona’s citizens depended on being able to live in well-lit space circulated by clean air from the gardens that were to surround them.

Apart from the trees lining the streets and a garden in every block, each neighbourhood would have a big park between four and eight blocks in size, with three hospitals to be laid out within each district network.

Although at the time it was impossible to imagine the existence of the motor vehicle, he created spacious streets to allow for the circulation of wagons, carts and horse trams.

Definitively Cerdà wanted to make a city fit for living, avoiding the state of overcrowding to be found in the old city.